Trigonometry in Galois fields

In mathematics, trigonometry analogies are supported by the theory of quadratic extensions of finite fields, also known as Galois fields. The main motivation to deal with a finite field trigonometry is the power of the discrete transforms, which play an important role in engineering and mathematics. Significant examples are the well-known discrete trigonometric transforms (DTT), namely the discrete cosine transform and discrete sine transform, which have found many applications in the fields of digital signal and image processing. In the real DTTs, inevitably, rounding is necessary, because the elements of its transformation matrices are derived from the calculation of sines and cosines. This is the main motivation to define the cosine transform over prime finite fields. In this case, all the calculation is done using integer arithmetic.

In order to construct a finite field transform that holds some resemblance with a DTT or with a discrete transform that uses trigonometric functions as its kernel, like the discrete Hartley transform, it is firstly necessary to establish the equivalent of the cosine and sine functions over a finite structure.

Contents |

Trigonometry over a Galois field

The set GI(q) of gaussian integers over GF(q) plays an important role in the trigonometry over finite fields (hereafter the symbol := denotes equal by definition).

- GI(q) := {a + jb, a, b ∈ GF(q)} q = pr,

r being a positive integer, p being an odd prime for which j2 = −1 is a quadratic non-residue in GF(q); it is a field isomorphic to GF(q2).

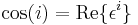

Trigonometric functions over the elements of a Galois field can be defined as follows:

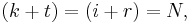

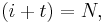

Let  be an element of multiplicative order N in GI(q), q = pr, p an odd prime such that p

be an element of multiplicative order N in GI(q), q = pr, p an odd prime such that p  3 (mod 4). The GI(q)-valued k-trigonometric functions of (

3 (mod 4). The GI(q)-valued k-trigonometric functions of (

) in GI(q) (by analogy, the trigonometric functions of k times the "angle" of the "complex exponential"

) in GI(q) (by analogy, the trigonometric functions of k times the "angle" of the "complex exponential"  i) are defined as

i) are defined as

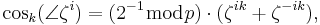

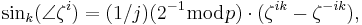

for i, k = 0, 1,...,N − 1. We write cosk( i) and sink (

i) and sink ( i) as cosk(i) and sink(i), respectively. The trigonometric functions above introduced satisfy properties P1-P12 below, in GI(p).

i) as cosk(i) and sink(i), respectively. The trigonometric functions above introduced satisfy properties P1-P12 below, in GI(p).

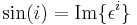

- P1. Unit circle:

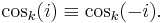

- P2. Even/Odd:

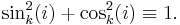

- P3. Euler formula:

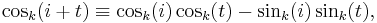

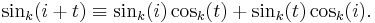

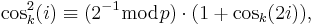

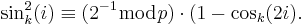

- P4. Addition of arcs:

- P5. Double arc:

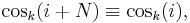

- P6. Symmetry:

- P7. Complementary symmetry: with

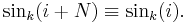

- P8. Periodicity:

- P9. Complement: with

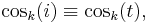

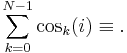

- P10.

summation:

summation:

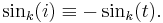

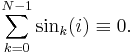

- P11.

summation:

summation:

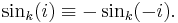

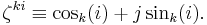

- P12. Orthogonality:

![\sum_{k=0}^{N-1}[\cos_k(i)\sin_k(t)]\equiv 0.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4ba891743e77e97c7986c6cab3f55f40.png)

Examples

- With ζ = 3, a primitive element of GF(7), then cosk(i) and sink(i) functions take the following values in GI(7):

| cosk(i) | sink(i) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 (i) | 0 1 2 3 4 5 (i) | ||

| 0 | 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 0 | 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

| 1 | 1 4 3 6 3 4 | 1 | 0 j j 0 6j 6j |

| 2 | 1 3 3 1 3 3 | 2 | 0 j 6j 0 j 6j |

| 3 | 1 6 1 6 1 6 | 3 | 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

| 4 | 1 3 3 1 3 3 | 4 | 0 6j j 0 6j j |

| 5 | 1 4 3 6 3 4 | 5 | 0 6j 6j 0 j j |

| (k) | (k) |

- Let ζ = j, an element of order 4 in GI(3). The cosk(i) and sink(i) functions take the following values in GI(3):

| cosk(i) | sink(i) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 1 2 3 (i) | 0 1 2 3 (i) | ||

| 0 | 1 1 1 1 | 0 | 0 0 0 0 |

| 1 | 1 0 2 0 | 1 | 0 1 0 2 |

| 2 | 1 2 1 2 | 2 | 0 0 0 0 |

| 3 | 1 0 2 0 | 3 | 0 2 0 1 |

| (k) | (k) |

Unimodular groups

The unimodular set of GI(p), denoted by G1, is the set of elements ζ = (a + jb) ∈ GI(p), such that a2 + b2  1 (mod p).

1 (mod p).

To determine the elements of the unimodular group it helps to observe that if ζ = a + jb is one such element, then so is every element in the set ζ = {b + ja, (p − a) + jb, b + j(p − a), a +j(p − b), (p − b) + ja, (p − a) + j(p − b), (p − b) + j(p − a)}.

Example

Unimodular groups of GF(72) and GF(112). In each case, table III lists the elements of the subgroups G1 of order 8 and 12, and their orders.

GI(7) GI(7) |

Order |  GI(11) GI(11) |

Order |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| −1 | 2 | −1 | 2 |

| j, −j | 4 | 5 + j3, 5 + j8 | 3 |

| 2 + j2, 2 + j5, 5 + j2, 5 + j5 | 8 | j, −j | 4 |

| 6 + j8, 6 + j3 | 6 | ||

| 8 + j6, 8 + j5, 3 + j6, 3 + j5 | 12 |

Figure 1 illustrates the 12 roots of unity in GF(112). Clearly, G1 is isomorphic to C12, the group of proper rotations of a regular dodecagon.  =8+j6 is a group generator corresponding to a counter-clockwise rotation of 2π/12 = 30°. Symbols of the same colour indicate elements of same order, which occur in conjugate pairs.

=8+j6 is a group generator corresponding to a counter-clockwise rotation of 2π/12 = 30°. Symbols of the same colour indicate elements of same order, which occur in conjugate pairs.

Polar form

Let Gr and Gθ be subgroups of the multiplicative group of the nonzero elements of GI(p), of orders (p − 1)/2 and 2(p + 1), respectively. Then all nonzero elements of GI(p) can be written in the form ζ = α·β, where α ∈ Gr and β ∈ Gθ.

Considering that any element of a cyclic group can be written as an integral power of a group generator, it is possible to set r = α and εθ = β, where ε is a generator of  . The powers εθ of this element play the role of ejθ over the complex field. Thus, the polar representation assumes the desired form,

. The powers εθ of this element play the role of ejθ over the complex field. Thus, the polar representation assumes the desired form,  , where r plays the role of the modulus of ζ. Therefore, it is necessary to define formally the modulus of an element in a finite field. Considering the nonzero elements of GF(p), it is a well-known fact that half of them are quadratic residues of p. The other half, those that do not possess square root, are the quadratic non-residue (in the field of real numbers, the elements are divided into positive and negative numbers, which are, respectively, those that possess and do not possess a square root).

, where r plays the role of the modulus of ζ. Therefore, it is necessary to define formally the modulus of an element in a finite field. Considering the nonzero elements of GF(p), it is a well-known fact that half of them are quadratic residues of p. The other half, those that do not possess square root, are the quadratic non-residue (in the field of real numbers, the elements are divided into positive and negative numbers, which are, respectively, those that possess and do not possess a square root).

The standard modulus operation (absolute value) in  always gives a positive result.

always gives a positive result.

By analogy, the modulus operation in GF(p) is such that it always results in a quadratic residue of p.

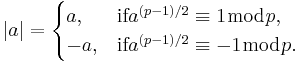

The modulus of an element  , where p = 4k + 3, is

, where p = 4k + 3, is

The modulus of an element of GF(p) is a quadratic residue of p.

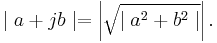

The modulus of an element a + jb ∈ GI(p), where p = 4k + 3, is

In the continuum, such expression reduces to the usual norm of a complex number, since both, a2 + b2 and the square root operation, produce only nonnegative numbers.

- The group of modulus of GI(p), denoted by Gr, is the subgroup of order (p − 1)/2 of GI(p).

- The group of phases of GI(p), denoted by G

, is the subgroup of order 2(p + 1) of GI(p).

, is the subgroup of order 2(p + 1) of GI(p).

An expression for the phase  as a function of a and b can be found by normalising the element

as a function of a and b can be found by normalising the element  (that is, calculating

(that is, calculating  ), and then solving the discrete logarithm problem of

), and then solving the discrete logarithm problem of  /r in the base

/r in the base  over GF(p). Thus, the conversion rectangular to polar form is possible.

over GF(p). Thus, the conversion rectangular to polar form is possible.

The similarity with the trigonometry over the field of real numbers is now evident: the modulus belongs to GF(p) (the modulus is a real number) and is a quadratic residue (a positive number), and the exponential component

) has modulus one and belongs to GI(p) (e

) has modulus one and belongs to GI(p) (e also has modulus one and belongs to the complex field

also has modulus one and belongs to the complex field  ).

).

The Z plane in a Galois field

The complex Z plane (Argand diagram) in GF(p) can be constructed from the supra-unimodular set of GI(p):

- The supra-unimodular set of GI(p), denoted Gs, is the set of elements ζ = (a + jb) ∈ GI(p), such that (a2 + b2)

−1 (mod p).

−1 (mod p). - The structure <Gs,*>, is a cyclic group of order 2(p + 1), called the supra-unimodular group of GI(p).

The elements ζ = a + jb of the supra-unimodular group Gs satisfy (a2 + b2)2 1 (mod p) and all have modulus 1. Gs is precisely the group of phases

1 (mod p) and all have modulus 1. Gs is precisely the group of phases  .

.

- If p is a Mersenne prime (p = 2n − 1, n > 2), the elements ζ = a + jb such that a2 + b2

−1 (mod p) are the generators of Gs.

−1 (mod p) are the generators of Gs.

Examples

- Let p = 31, a Mersenne prime, and ζ = 6 + j16. Then

7 (mod 31), so that

7 (mod 31), so that  /r = 23 + j20 and a2 + b2 = 232 + 202

/r = 23 + j20 and a2 + b2 = 232 + 202 −1 (mod 31). Therefore ε has order 2(p + 1) = 64 (a generator). A unimodular element β of order N, such that N | 25, can be found taking

−1 (mod 31). Therefore ε has order 2(p + 1) = 64 (a generator). A unimodular element β of order N, such that N | 25, can be found taking  2(p+1)/N =

2(p+1)/N =  .

.

- The Z plane in GF(7): With p = 7, and ζ = 6 + j4,

2 (mod 31), so that ε = ζ/r = 3 + j2 and a2 + b2 = 13

2 (mod 31), so that ε = ζ/r = 3 + j2 and a2 + b2 = 13 −1 (mod 31). Therefore ε has order 2(p + 1) = 16, so it is a generator of the group Gs.

−1 (mod 31). Therefore ε has order 2(p + 1) = 16, so it is a generator of the group Gs.

A generator ε of the supra-unimodular group is used to construct the Z plane over GF(p). The Z plane over GF(7) is depicted in figure 2. There are 2(p + 1) = 16 elements in each circle. The nonzero elements, namely ±1, ±2, ±3, are located on the horizontal axis, in the right or left side, according if they are, respectively, quadratic residues (QR) or quadratic non-residues (NQR) of p = 7. There are three circles, of radius 1, 2 and 4, corresponding to the (p − 1)/2 = 3 elements of the group of modules Gr. A similar situation occurs for the elements of GI(7) of the form jb. The 16 elements on the unit circle correspond to the elements of Gs and are obtained as powers of ε. The even powers correspond to the elements of G1 (a2 + b2  1 (mod 7)) and the odd powers to the elements satisfying a2 + b2

1 (mod 7)) and the odd powers to the elements satisfying a2 + b2  −1 (mod 7). The remaining 32 elements of the Z plane are obtained simply by multiplying those on the unit circle by the modulus 2 and 4. The elements on the straight line y=±x over a finite field also possesses the usual interpretation associated with tg

−1 (mod 7). The remaining 32 elements of the Z plane are obtained simply by multiplying those on the unit circle by the modulus 2 and 4. The elements on the straight line y=±x over a finite field also possesses the usual interpretation associated with tg  = ±1.

= ±1.

The number of elements of a given order as elements of GI(7) in the z plane over GF(7) is given in the inset of figure 2.

Back to the GF(p)-trigonometry

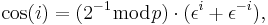

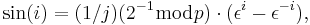

In the above, if the choice of  is careless, the trigonometric functions may possibly be complex, i.e., they may be GI(p)-valued. However, if

is careless, the trigonometric functions may possibly be complex, i.e., they may be GI(p)-valued. However, if  =a+jb is chosen to be a unimodular element, so that a2+b2

=a+jb is chosen to be a unimodular element, so that a2+b2 1 (mod p), then cos(.) and sin(.) are GF(p)-valued. With that in mind and dropping a few subscripts, the definitions may be rephrased in a simpler form as:

1 (mod p), then cos(.) and sin(.) are GF(p)-valued. With that in mind and dropping a few subscripts, the definitions may be rephrased in a simpler form as:

for i = 0, 1, ..., p. The k subscript in the earlier definition gives an unexpected two-dimensional character to the cos(.) and sin(.) functions. As a matter of fact, it means only that to compute the entries in tables I and II, a different value of  =

=  k was used for each k. These k-trigonometric functions lead to sequences with interesting orthogonality properties which may be used to construct new finite field transforms.

k was used for each k. These k-trigonometric functions lead to sequences with interesting orthogonality properties which may be used to construct new finite field transforms.

Now, to play with a trigonometry over GF(7) on the unit circle, it seems much more natural to use, for instance,  = 2 + j2

= 2 + j2 GI(7), instead of

GI(7), instead of  = 3 ∈ GF(7) as in table I (examples). In this case, |

= 3 ∈ GF(7) as in table I (examples). In this case, | | = 1 and both cos and sin are "real-valued" functions, as expected.

| = 1 and both cos and sin are "real-valued" functions, as expected.

Further, if  is chosen from the set of unimodular elements, it can be shown that the "real" part of

is chosen from the set of unimodular elements, it can be shown that the "real" part of  is equal to the "real" part of

is equal to the "real" part of  , and the "imaginary" part of

, and the "imaginary" part of  is equal to the negative of the "imaginary" part of

is equal to the negative of the "imaginary" part of  . So, for unimodular element

. So, for unimodular element  , the definitions simplify to:

, the definitions simplify to:

Example

With  = 2 + j2, a unimodular element of order p + 1 = 8 of GI(7), the cos(i) and sin(i) functions take the following values in GF(7):

= 2 + j2, a unimodular element of order p + 1 = 8 of GI(7), the cos(i) and sin(i) functions take the following values in GF(7):

| (i) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cos(i) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| sin(i) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

Trajectories over the Galois Z plane in GF(p)

When calculating the order of a given element, the intermediate results generate a trajectory on the Galois Z plane, called the order trajectory. In particular, If  has order N, the trajectory goes through N distinct points on the Z plane, moving in a pattern that depends on N. Specifically, the order trajectory touches on every circle of the Galois Z plane (there are ||Gr|| of them), in order of increasing modulus, always returning to the unit circle. If it starts on a given radius, say R, it will visit, counter-clockwise, every radius of the form R+k.r, where r=(p2−1)/N and k = 0, 1, 2, ....., N − 1. Given a prime p

has order N, the trajectory goes through N distinct points on the Z plane, moving in a pattern that depends on N. Specifically, the order trajectory touches on every circle of the Galois Z plane (there are ||Gr|| of them), in order of increasing modulus, always returning to the unit circle. If it starts on a given radius, say R, it will visit, counter-clockwise, every radius of the form R+k.r, where r=(p2−1)/N and k = 0, 1, 2, ....., N − 1. Given a prime p  3 (mod 4), there are a (finite) number of (p − 1)/2 distinct circles over the Galois Z plane GI(p), and the number of distinct finite field ellipses is (p − 1).(p − 3)/4.

3 (mod 4), there are a (finite) number of (p − 1)/2 distinct circles over the Galois Z plane GI(p), and the number of distinct finite field ellipses is (p − 1).(p − 3)/4.

- Table V lists some elements ζ ∈ GI(7) and their orders N. Figures 3–5 show the order trajectories generated by ζ.

|

2j | 3 + 3j | 6 + 4j |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 12 | 24 | 48 |

References

- R. M. Campello de Souza, H. M. de Oliveira and A. N. Kauffman, "Trigonometry in Finite Fields and a New Hartley Transform," Proceedings of the 1998 International Symposium on Information Theory, p. 293, Cambridge, MA, Aug. 1998.

- M. M. Campello de Souza, H. M. de Oliveira, R. M. Campello de Souza and M. M. Vasconcelos, "The Discrete Cosine Transform over Prime Finite Fields," Lecture Notes in Computer Science, LNCS 3124, pp. 482–487, Springer Verlag, 2004.

- R. M. Campello de Souza, H. M. de Oliveira and D. Silva, "The Z Transform over Finite Fields," International Telecommunications Symposium, Natal, Brazil, 2002.

- "Tools: Mathematical Matlab Routines". Federal University of Pernambuco. 2003-06-23. http://www2.ee.ufpe.br/codec/FFtools.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-12.